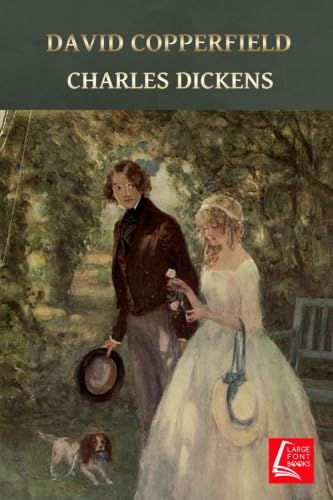

Author: Dickens, Charles

Price: $21.00

Category:European Literature

Publication Date:2018-02-17T00:00:01Z

Pages:606

Binding:Paperback

ISBN:10:1985646358

ISBN:13:9781985646353

My father had once been a favourite of hers, I believe; but she was mortallyaffronted by his marriage, on the ground that my mother was ‘a wax doll’. Shehad never seen my mother, but she knew her to be not yet twenty. My father andMiss Betsey never met again. He was double my mother’s age when he married,and of but a delicate constitution. He died a year afterwards, and, as I have said,six months before I came into the world.This was the state of matters, on the afternoon of, what I may be excused forcalling, that eventful and important Friday. I can make no claim therefore tohave known, at that time, how matters stood; or to have any remembrance,founded on the evidence of my own senses, of what follows.My mother was sitting by the fire, but poorly in health, and very low inspirits, looking at it through her tears, and desponding heavily about herself andthe fatherless little stranger, who was already welcomed by some grosses ofprophetic pins, in a drawer upstairs, to a world not at all excited on the subjectof his arrival; my mother, I say, was sitting by the fire, that bright, windy Marchafternoon, very timid and sad, and very doubtful of ever coming alive out of thetrial that was before her, when, lifting her eyes as she dried them, to the windowopposite, she saw a strange lady coming up the garden.My mother had a sure foreboding at the second glance, that it was MissBetsey. The setting sun was glowing on the strange lady, over the garden-fence,and she came walking up to the door with a fell rigidity of figure and composureof countenance that could have belonged to nobody else.When she reached the house, she gave another proof of her identity. Myfather had often hinted that she seldom conducted herself like any ordinaryChristian; and now, instead of ringing the bell, she came and looked in at thatidentical window, pressing the end of her nose against the glass to that extent,that my poor dear mother used to say it became perfectly flat and white in amoment.She gave my mother such a turn, that I have always been convinced I amindebted to Miss Betsey for having been born on a Friday.My mother had left her chair in her agitation, and gone behind it in thecorner. Miss Betsey, looking round the room, slowly and inquiringly, began onthe other side, and carried her eyes on, like a Saracen’s Head in a Dutch clock,until they reached my mother. Then she made a frown and a gesture to mymother, like one who was accustomed to be obeyed, to come and open the door.My mother went.’Mrs. David Copperfield, I think,’ said Miss Betsey; the emphasis referring,perhaps, to my mother’s mourning weeds, and her condition.’Yes,’ said my mother, faintly.’Miss Trotwood,’ said the visitor. ‘You have heard of her, I dare say?’My mother answered she had had that pleasure. And she had a disagreeableconsciousness of not appearing to imply that it had been an overpoweringpleasure.’Now you see her,’ said Miss Betsey. My mother bent her head, and beggedher to walk in.They went into the parlour my mother had come from, the fire in the bestroom on the other side of the passage not being lighted-not having beenlighted, indeed, since my father’s funeral; and when they were both seated, andMiss Betsey said nothing, my mother, after vainly trying to restrain herself,began to cry. ‘Oh tut, tut, tut!’ said Miss Betsey, in a hurry. ‘Don’t do that!Come, come!’My mother couldn’t help it notwithstanding, so she cried until she had hadher cry out.’Take off your cap, child,’ said Miss Betsey, ‘and let me see you.’My mother was too much afraid of her to refuse compliance with this oddrequest, if she had any disposition to do so. Therefore she did as she was told,and did it with such nervous hands that her hair (which was luxuriant andbeautiful) fell all about her face.’Why, bless my heart!’ exclaimed Miss Betsey. ‘You are a very Baby!’